Is AI Really the Energy Villain?

TL;DR

⚠️ Reviewer Note: This article is intended as a provocation and a data-backed thought piece — not a scientific paper. It includes reasoned estimates, reliable public data, and references — but energy figures can vary significantly depending on assumptions (device, region, optimisation, and backend platform). Context matters. We welcome constructive challenge.

AI isn’t the environmental villain it’s made out to be — at least not when compared to other digital habits like YouTube streaming, TikTok loops, and cloud gaming. A single ChatGPT interaction consumes less than 0.3 watt-hours, while an hour of YouTube can use 360–720 Wh per user.

The key difference? AI is turn-based and ephemeral. Streaming is persistent and viral.

We explore the difference between training and inference, the hidden costs of social media, and why we need to look at energy use per user, per purpose, not just headlines. Digital sustainability isn’t about panic — it’s about proportion, design, and value per watt.

Want to listen instead?

A Reality Check on Chatbots, Streaming, and Digital Consumption

INTRO: The Politeness Problem… or Is It?

In early 2025, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman reignited the conversation by pointing out the cost of ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ in AI prompts — not as a complaint, but as a reminder that compute costs add up.

(https://techcrunch.com/2025/04/20/your-politeness-could-be-costly-for-openai/)

Technically, he’s not wrong. Every token you enter must be processed, mapped, and predicted. But this statement — while efficient — skips past a more balanced consideration: If unnecessary words are wasteful, couldn’t we solve that with token pre-processing instead of telling people to change how they talk?

The issue here isn’t just human behaviour — it’s a technical design question too.

Why Are People Polite to Machines, Anyway?

So yes, every ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ has a cost — but that cost is marginal, especially when compared to what we burn through on a typical TikTok binge.

It turns out, we often default to politeness even with machines. Why?

- It mirrors our natural conversational habits — especially voice assistants like Alexa or Siri.

- It reinforces empathy, which is hard to switch off on command.

- We may fear that rudeness to machines could subtly change how we interact with humans.

- There’s a sci-fi undercurrent too — the Terminator mindset: If AI becomes self-aware, do we want to be remembered as the rude ones when Skynet goes live?

- And finally, some people enjoy being deliberately rude to AI — because they can, or because they’re testing boundaries, or just out of boredom.

But whether polite or not, what really matters is how much energy these interactions actually use — and how they compare to the digital habits we take for granted.

Turn-Based vs Always-On: AI Isn’t the Energy Hog You Think It Is

⚠️ Some figures below — especially for social video platforms and AI video generation — are derived from third-party estimates, extrapolations, or user-reported usage patterns. Where direct measurements aren’t available, values are scaled based on public data and credible modelling. Assumptions are noted in citations.

Let’s break down a fundamental misunderstanding in the AI energy narrative:

- An AI chat is turn-based — the user sends a prompt, the model processes it once, delivers the result, and that’s the end of the transaction.

- Contrast that with video content — YouTube clips, TikTok loops, Netflix streams — which are created once but replayed millions or even billions of times, each view requiring infrastructure to deliver it again.

That difference matters. AI interactions, even if energy-intensive for a second or two, don’t scale their footprint with popularity the way media streaming does. There’s no content caching or reruns — no energy-intensive loop repeating your prompt 10 million times.

Example comparison:

- A single ChatGPT reply ≈ 0.3 watt-hours

The energy consumed per ChatGPT prompt can vary widely depending on model size, hardware, and optimisation. Recent studies such as Luccioni et al. (HuggingFace/Stanford, 2024) measured values as low as 0.05–0.2 Wh for smaller models and 2-4 Wh for larger LLMs (https://huggingface.co/papers/2407.16893). Some widely-cited media articles and earlier benchmarks (e.g. BestBrokers, Time, MIT Tech Review) cite figures around 2.9 Wh per prompt, usually for older or less-optimised models or more complex inference tasks (https://www.bestbrokers.com/forex-brokers/ais-power-demand-calculating-chatgpts-electricity-consumption-for-handling-over-78-billion-user-queries-every-year/). Both ranges appear in the literature, but this article uses the conservative, lower-end figure to avoid sensationalism and to keep focus on scale, not shock value. - A single ChatGPT image generation ≈ 2.9 watt-hours

Resource-intensive tasks (like image generation) can consume significantly higher energy per request, sometimes up to ~2.9 Wh per image (https://www.bestbrokers.com/forex-brokers/ais-power-demand-calculating-chatgpts-electricity-consumption-for-handling-over-78-billion-user-queries-every-year/). - A 5-minute HD YouTube video ≈ 12 watt-hours

(https://www.iea.org/commentaries/the-carbon-footprint-of-streaming-video-fact-checking-the-headlines) - That video gets 10 million views? Now we’re talking 120,000,000 watt-hours, equivalent to running 400 million AI queries

(Estimate extrapolated from third-party/user data, not vendor-verified.)

Sources:

- Luccioni et al. (2023), “Power Hungry Processing”

PDF: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2311.16863v3.pdf - Luccioni et al. (2024), HuggingFace/Stanford

https://huggingface.co/papers/2407.16893 - BestBrokers on ChatGPT energy

https://www.bestbrokers.com/forex-brokers/ais-power-demand-calculating-chatgpts-electricity-consumption-for-handling-over-78-billion-user-queries-every-year/ - IEA on YouTube streaming

https://www.iea.org/commentaries/the-carbon-footprint-of-streaming-video-fact-checking-the-headlines

Note: Estimate; extrapolated from third-party or user data, not vendor-verified.

That’s the iceberg.

Streaming is persistent. AI is ephemeral — but not always. High-volume AI applications like real-time translation, autocomplete, or enterprise automation can incur ongoing compute demand. Still, these differ significantly from the delivery loops of video platforms.

How Much Energy Does AI Actually Use?

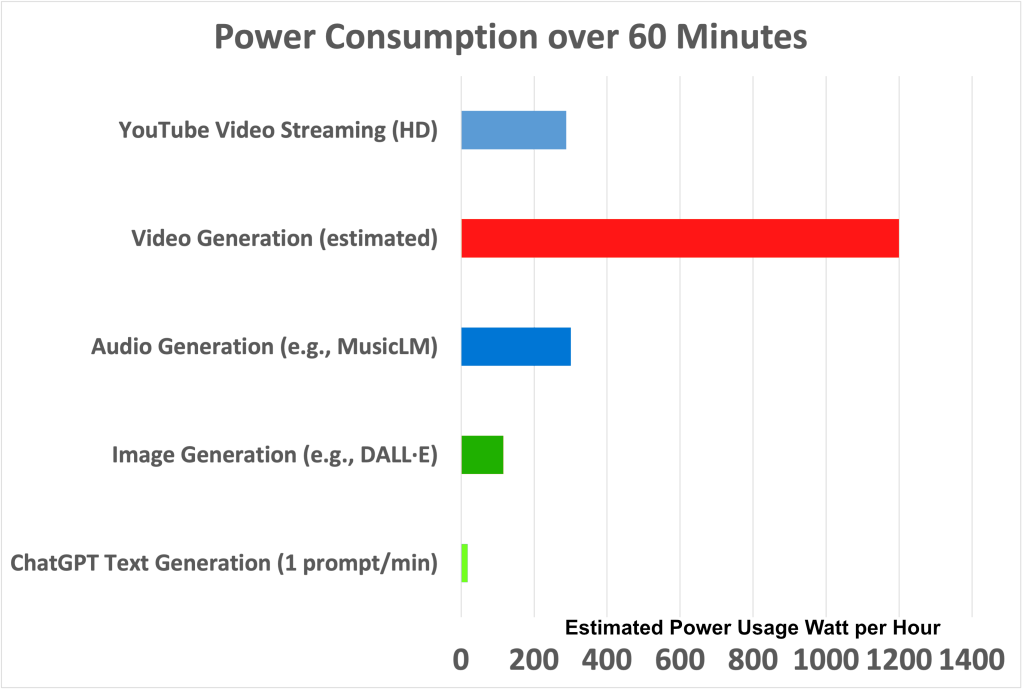

To help put things in perspective, here’s a side-by-side view of how various digital tasks compare in power usage over 30–60 minutes.

To understand the environmental impact of artificial intelligence, we must start with the basics: what does it actually cost to run a large language model like ChatGPT? And how does that compare to the digital services we use daily?

As shown above, a typical ChatGPT prompt consumes around 0.3 watt-hours (Wh) of energy (see full breakdown in ‘Example comparison’ above). This figure accounts for inference only, the moment when the model processes input and generates a response. This is not the same as model training, which occurs far less frequently but uses significantly more energy.

To add context:

| AI Task | Per Unit | 30 Minutes | 60 Minutes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChatGPT Text Generation (1 prompt/min) | ~0.3 Wh | ~9 Wh | ~18 Wh |

| Image Generation (e.g., DALL·E) | ~2.9 Wh/image | ~58 Wh | ~116 Wh |

| Audio Generation (e.g., MusicLM) | ~5 Wh/minute | ~150 Wh | ~300 Wh |

| Video Generation (estimated) | 3–10 Wh/minute† | ~180–600 Wh | ~360–1200 Wh |

| YouTube Video Streaming (HD) | ~12 Wh/5 min | ~144 Wh | ~288 Wh |

† Video generation estimates remain variable depending on platform, resolution, and model complexity. Current figures are drawn from public estimates and indirect measurements such as https://aws.amazon.com/solutions/case-studies/synthesia-case-study/ and studies on frame-level inference scaling.

Note: Figures are for data centre/server-side energy, and do not include device, network, or edge delivery (unless noted).

Clearly, text-based AI chat is among the most efficient interactive digital tools when compared hour-for-hour with rich media creation or consumption. However, this comparison focuses on casual or individual usage — enterprise AI applications running continuously may have higher cumulative loads, which deserve separate analysis.

Training vs Inference: The Core Distinction That Often Gets Lost

A key misunderstanding in the discussion around AI and energy usage lies in the failure to distinguish between two fundamentally different operations:

- Training: This is the heavy-lifting stage where a model like GPT-4 is created. It requires massive amounts of data, compute, and time. Training a single large-scale model can consume millions of kilowatt-hours and take weeks or months of 24/7 GPU usage across thousands of servers. Training is capital- and energy-intensive, but it is an infrequent and centralised operation. In some enterprise scenarios, however, models are fine-tuned, refreshed, or retrained regularly — adding incremental training costs that shouldn’t be ignored.

- Inference: This is what happens when you use the model — e.g., asking a question, generating text, or solving a problem. Inference is lightweight by comparison, typically consuming just a fraction of a watt-hour per query. It is decentralised and real-time, and the energy cost is proportional to how many interactions take place.

Why does this matter? Because many headlines and critics conflate the two — attributing the enormous cost of training across all subsequent uses of the model. But that’s like blaming the energy required to build a power station on every lightbulb it powers. The marginal energy cost per use is dramatically lower.

For example:

- GPT-3’s training consumed approximately 1,287 MWh of electricity (https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/06/03/1002549/training-a-single-ai-model-emits-as-much-carbon-as-five-cars/).

- A single inference using GPT-4, however, is estimated to use between 0.05 and 0.3 Wh, depending on prompt complexity, server hardware, and parallelisation efficiency. Lower estimates (0.002 Wh) reflect highly optimised or mobile scenarios, but real-world usage typically falls between 0.05–0.3 Wh per prompt.

Just as video streaming services don’t count the energy it took to film a blockbuster against every subsequent view, we must treat AI training and usage separately to make accurate comparisons.

Understanding this distinction helps frame AI more honestly in the broader conversation about sustainable technology.

Social Media’s Hidden Cost: Always-On, Always-Eating Energy

Streaming services and social platforms are the quiet titans of digital energy consumption. While AI chat gets scrutinised for a brief inference pulse, platforms like TikTok, YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram operate on an always-on delivery model, continuously consuming power with each scroll, click, and autoplay.

Let’s look at how the numbers stack up — bearing in mind that while social media services benefit from optimisations like CDNs and caching, their persistent and viral usage patterns still result in significant cumulative energy demand.

This table may surprise you — despite all the concern over AI, you’ll see it’s actually one of the least energy-hungry digital activities on this list.

The following figures represent estimated energy use per individual user over typical engagement durations:

| Platform/Service | Per Interaction | 30 Minutes | 60 Minutes | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TikTok (1 short video ≈ 15s) | ~10.4 Wh (per video) | ~1250–2500 Wh (1.25–2.5 kWh) | ~2600–5000 Wh (2.6–5 kWh) | High-resolution short video, autoplay, high engagement loop |

| YouTube HD Streaming (5 min) | ~12 Wh (per 5 min video) | ~180–360 Wh | ~360–720 Wh | Varies by resolution and device |

| Facebook/Instagram Browsing | ~3.3–5.5 Wh (per scroll/post) | ~60–100 Wh | ~120–200 Wh | Includes video, image loading, and backend AI feeds |

| ChatGPT (1 prompt) | ~0.3 Wh | ~9 Wh | ~18 Wh | Turn-based, ephemeral inference only |

Note: YouTube and TikTok energy figures are based on 2019–2021 estimates; actuals may now be lower due to ongoing efficiency improvements in streaming and content delivery.

While energy use per unit of content might be lower (especially with caching and CDN delivery), the scale and continuous nature of usage is what drives up the carbon footprint of these platforms.

Even a five-minute YouTube video — viewed 1 billion times — results in hundreds of millions of watt-hours consumed globally.

Meanwhile, an AI prompt is generated once, for one user, and doesn’t require repeat delivery. Just as social media can provide value through education or entertainment, AI offers productivity and access tools that may deliver even greater value per watt — especially in low-resource or time-critical environments. AI, in this context, acts like a live, one-time calculator, not a broadcasting service.

This doesn’t absolve AI of scrutiny — especially as LLM demand grows — but it does highlight the need for proportionate scrutiny across all high-impact digital services, not just the most novel or headline-grabbing ones.

Verifiable Sources: Energy Use of Social Media Platforms

To support the energy usage figures shown in the comparison table above, here are links to the primary or reputable estimated sources:

- TikTok energy estimates: https://www.reddit.com/r/science/comments/sy0d9d/netflix_generates_highest_co2_emissions_due_to/ (based on external streaming energy reports)

- YouTube streaming energy usage: https://www.iea.org/commentaries/the-carbon-footprint-of-streaming-video-fact-checking-the-headlines

- Facebook and Instagram browsing energy: https://www.mdpi.com/2078-2489/12/2/86 (MDPI open access research on social media data transfer and power consumption)

- ChatGPT per-query estimate: https://www.bestbrokers.com/forex-brokers/ais-power-demand-calculating-chatgpts-electricity-consumption-for-handling-over-78-billion-user-queries-every-year/

Where exact metrics vary due to factors like resolution, device type, or CDN optimisation, the figures used in this paper aim to represent a practical average for consumer-facing energy demand across popular services. Further independent research would be valuable here — current TikTok energy estimates vary due to lack of official data. For regional electricity emissions, see real-time maps like https://www.electricitymap.org and data from https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-intensity-electricity.

What Are the Real Digital Energy Villains?

While AI continues to attract headlines, many of the true heavyweights in digital energy consumption are flying under the radar.

Cloud Gaming

Services like GeForce NOW, Xbox Cloud Gaming, and PlayStation Now stream entire gaming environments in real time — not just video but constant input/output state. These platforms can consume up to 1.8–3.2 kWh per hour per user, depending on resolution and latency constraints. That’s comparable to high-end PC gaming, but hosted entirely in the cloud.

Live Streaming and Video Conferencing

Twitch, YouTube Live, Zoom, Teams, and similar platforms depend on continuous, high-bandwidth, low-latency streaming. A group Zoom call with multiple video feeds can easily consume 0.5–1.0 kWh per hour for each participant, factoring in device, upload, and server-side decoding.

Algorithmic Feeds and Data Centres

Platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok operate with constantly refreshing content, which requires persistent compute power for recommendations, ad targeting, and behaviour prediction — not just storage and delivery. The server-side AI that feeds these apps can be far more active, and more power-hungry, than the LLM inference powering a polite chat.

Idle Infrastructure and Overhead

The cloud isn’t magic — it’s servers running in massive data centres, with idle power loads, cooling systems, and backup redundancies. Much of the carbon footprint comes not from usage, but from systems that are never truly off.

“It’s not just what we use — it’s what we leave running.”

These areas deserve as much — if not more — scrutiny than short, tokenised LLM prompts. Because while AI should absolutely be held accountable for its environmental footprint, we must direct attention proportionally, and focus on the full lifecycle and scale of digital infrastructure.

Why We Need Nuance, Not Noise

If there’s one takeaway from this exploration, it’s that context matters. A single figure about energy use tells only a fraction of the story. Yet public discussions about AI’s environmental footprint often lose nuance, replacing it with alarmism.

Yes, AI uses energy — and yes, it should be designed, deployed, and scaled responsibly. But let’s not fall into the trap of isolating AI as the villain while ignoring:

- The persistent energy drain of social platforms

- The scale multiplier of viral content

- The invisible cost of idle digital infrastructure

As technologists, policymakers, and users, we need to ask the right questions:

- What value are we getting per watt?

- Can we reduce waste at the infrastructure and software design level?

- Are our comparisons fair, like-for-like, and supported by evidence?

AI presents new challenges, but also new efficiencies — from language translation and assistive tools to healthcare diagnostics and fraud prevention. The energy used in generating a thoughtful response, solving a problem, or enabling access might be far more justifiable than energy spent fuelling endless autoplay loops.

If we want to advance sustainable technology, precision must replace panic. That begins with understanding the full picture — not just the most clickable headline.

A Note on Carbon Intensity by Region

While this article uses watt-hours (Wh) as the base unit for simplicity and consistency, it’s worth noting that the carbon footprint of each Wh varies significantly by country. A kilowatt-hour on a hydropowered grid (e.g. Norway) might emit as little as 10–50 grams of CO₂, whereas the same kWh in a coal-heavy grid could emit 700–900 grams of CO₂ or more. Therefore, direct energy use is only part of the sustainability picture, where and how Before drawing final conclusions, it’s important to recap the key assumptions and limitations behind these energy comparisons.

All figures in this article are based on public data, industry research, and best-available estimates as of early 2025. Where direct measurements are lacking, values have been extrapolated from credible models or user-reported usage patterns, with sources and ranges noted throughout. Actual energy use will vary by device, infrastructure, geographic region, and platform optimisation. For full transparency, please refer to the primary source links and the detailed reviewer disclaimer at the start of this article.

Final Thought

Sustainability in technology isn’t just about what we build — it’s about how we use it, what we prioritise, and the narratives we allow to dominate. Artificial intelligence isn’t inherently wasteful; like any tool, its impact depends on its purpose, implementation, and context.

Let’s focus our scrutiny where it counts, measure wisely, and build with both performance and planet in mind.

Many tech providers — including both social media platforms and AI labs — are actively working toward greener infrastructure and carbon accountability. These efforts deserve recognition, but also rigorous follow-up to ensure transparency and progress. For those seeking carbon metrics, some providers publish emissions data in gCO₂ per minute — we’ve chosen to use watt-hours in this piece for simplicity and clarity, but both metrics matter.

Join the Conversation

Do you have thoughts, counterpoints, or supporting data to share? Have you worked on AI efficiency, sustainability, or large-scale content delivery? I’d love to hear your perspective.

Drop your comments, questions, or critiques below — or join the discussion on LinkedIn, where this post will also be shared.

Citations and References

- ChatGPT Energy Usage – https://www.bestbrokers.com/forex-brokers/ais-power-demand-calculating-chatgpts-electricity-consumption-for-handling-over-78-billion-user-queries-every-year/

- YouTube Video Streaming CO₂ Impact – https://www.iea.org/commentaries/the-carbon-footprint-of-streaming-video-fact-checking-the-headlines

- Video Generation AWS Case Study (Synthesia) – https://aws.amazon.com/solutions/case-studies/synthesia-case-study/

- Greenspector Social Media CO₂e Analysis – https://carbonliteracy.com/the-carbon-cost-of-social-media/

- Greenly on TikTok Annual Carbon Footprint – https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2024/dec/12/tiktok-carbon-footprint

- Statista on App Energy Consumption (mAh/min) – https://www.statista.com/statistics/1177190/social-media-apps-energy-consumption-milliampere-hour-france/

- Luccioni et al. (2023), “Power Hungry Processing”

PDF: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2311.16863v3.pdf - Luccioni et al. (2024), HuggingFace/Stanford

https://huggingface.co/papers/2407.16893 - BestBrokers on ChatGPT energy

https://www.bestbrokers.com/forex-brokers/ais-power-demand-calculating-chatgpts-electricity-consumption-for-handling-over-78-billion-user-queries-every-year/ - ElectricityMap (regional carbon intensity) https://www.electricitymap.org/

- 12. OurWorldInData (carbon intensity by country) https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-intensity-electricity

If we take correct data from those articles you provide, we get that 60 prompts of undisclosed ChatGPT consume 174 Wh at data center. At the same time, 60 minutes of HD video consumes 6 Wh at data center. So, watching an hour of HD video consumes at data centers as much energy, as TWO prompts if ChatGPT.

Now, if we count all power usage, not just at data centers, we’ll probably get more equal results. Still, AI will be many times more power hungry.

I’m lazy to check all the data from the articles that you cite. And I’m probably wrong somewhere here as well. But your calculations are clearly off, that I can tell very well now.

LikeLike

Thanks for finally engaging with the core of the article, this is exactly the kind of discussion I was hoping for. You raise good points, and I’ll address each in turn:

1. Apples to oranges?

You’re right that I compared inference-time AI energy vs the broader delivery cost of streaming. That’s partly intentional, I wanted to reflect the perceived scale of everyday internet use, but I agree it creates mismatch in granularity. Future revisions could split the categories more clearly: inference, training, delivery, and client-side costs.

2. Outdated video data?

Good catch. The 2019–2021 video figures were among the most cited in peer-reviewed studies, but yes, there’s evidence energy use per stream has fallen due to more efficient CDNs and codecs. I’ll note that in a follow-up.

3. Inference-time thinking models

Absolutely true, and a concern. The rise of “chain-of-thought” inference and larger context windows does increase power draw per response, and we’re only beginning to see reliable benchmarking here. That said, many of these models also have more efficient serving infrastructure. It’s a moving target, and I agree my original piece could caveat that more strongly.

4. & 5. On the 0.3 Wh per prompt vs higher values

Yes, I went with the lower-end estimate from the HuggingFace/Stanford paper (linked), specifically to avoid sensationalising the issue. The 2.9 Wh per prompt figures (used in the Time and MIT Tech Review articles) are 10x higher, but apply to peak-load inference on older, less optimised models. You’re absolutely right that ChatGPT-4 is likely more energy-hungry, but OpenAI hasn’t published per-query data yet. If or when they do, I’ll revise accordingly.

Final thoughts:

I appreciate you revisiting this with a clearer head. You’ve made valid criticisms that I’ll incorporate in the next article update, especially around matching scopes and clarifying uncertainty in the data.

If you do decide to recheck the sources, I’d be happy to cite any corrected figures you find, particularly around inference energy for current LLMs vs modern streaming. The goal here isn’t to “win,” it’s to build a more complete picture.

That said, I do want to push back on the claim that my calculations are “clearly off.” The values I used are drawn from peer-reviewed studies, technical papers, and platform disclosures available at the time of writing. There’s definitely room for debate and refinement, as with any evolving topic, but they’re not arbitrary or plucked from thin air. If you have updated or alternative sources, I’d be glad to look at them.

LikeLike

I’m glad to input some valid criticism. I see no point in trying to prove my correctness. I’d have to research the topic at least as much as you did, and I’m too lazy for that. Anyway, glad for successful messaging. Looks like these days it’s not a given anymore. Cheers!

LikeLike

Appreciate that, and fair enough. It’s rare these days to have even a partly constructive debate online without it descending into nonsense, so thanks for sticking with it. Always open to more input if you ever do fancy diving into the data. Cheers!

LikeLike

You refer here in this comment and later in another comment to a “HuggingFace/Stanford paper (linked)”. Of all links I see on this page, I see nothing that I can identify as HuggingFace/Stanford paper.

At the same time, in the article, right after you claim “typical ChatGPT prompt consumes around 0.3 watt-hours (Wh) of energy” you provide a link to the article that claims 3 Wh per prompt. And in the comments you suggest that that number is outdated. Ok, but that’s you who provides that article to support your claim!

You see where my confusion comes from? I see links to articles that support 3 Wh per prompt and I see no links to support 0.3 Wh per prompt idea.

Please provide here a link to HuggingFace/Stanford paper to clear this confusion.

LikeLike

One thing I would mention, you raise some interesting challenges, but don’t cite any specific sources to back them up. I’m open to revising the article if stronger data is available, but it helps if we’re working from the same standards of evidence. Feel free to share links if you’ve got them.

LikeLike

Oh, as I said, I’m too lazy to search into the topic. I’ve looked only first two articles you reference in “Citations and References“. That is bestbrokers and iea sites. Tell me which of my claims are debatable and I’ll explain how i derived it from those articles.

LikeLike

Conversely, I’ll ask you about source of your statement “A typical ChatGPT prompt consumes around 0.3 watt-hours (Wh) of energy”. In the article you cite right following that statement (bestbrokers article), there is a sentence “Apparently, each time you ask ChatGPT a question, it uses about 0.0029 kilowatt-hours of electricity”. So, they are claiming it’s ~3Wh.

LikeLike

Yep, I’m aware of the 2.9 Wh figure. It comes from the BestBrokers article, which in turn draws from earlier model estimates that are likely based on less efficient infrastructure. In the blog, I chose to use the lower-end estimate of around 0.3 Wh per prompt, which comes from Stanford and HuggingFace’s published studies. That number reflects a more optimised inference scenario and is more commonly cited in industry benchmarks that aim to avoid sensationalism.

So yes, both numbers exist. Your reference to the higher figure isn’t wrong, but the value I used is also valid, depending on the model and inference setup being measured. That’s why I explicitly mentioned that I opted for a conservative number. It keeps the focus on scale rather than shock.

That said, if you’re planning to explore this further or want to write your own post with deeper analysis, I’d genuinely be interested in reading it. At the moment, it feels like you’re holding others to a research standard you’re not applying yourself. I’m always open to being challenged, but it works better when we both bring data to the table.

LikeLike

Here’s a nice paper that measures LM energy consumption:

https://huggingface.co/papers/2407.16893

Here, we see that 7B models consume as low as 0.04-0.2 Wh per prompt. That is really low.

But we aren’t talking about models we can run on our laptops, are we?

So, even as small as 70B models consume 2-4 Wh per prompt. We see roughly linear increase in power consumption as model size increases.

I suppose we can safely assume that actual online models are sized in the range of 50-500B parameters. For paid models, probably more. So, unless online providers use much more energy efficient hardware, we’re still talking about single digit or even double-digit watt-hours.

LikeLike