Knights Tour

TL;DR

This blog explores the classic Knight’s Tour problem — moving a knight across a chessboard to visit every square exactly once. What started as a nostalgic puzzle turned into a fun Python project combining:

- ♞ Warnsdorff’s Rule (a fast but fallible heuristic)

- 🐢 Recursive backtracking for edge-case recovery

- 🧪 Validation logic to ensure each solution is sound

- 🖥️ ASCII terminal animation, inspired by retro systems like the CPX-16

- 🔥 Planned heatmaps to visualise constraint pressure and path dynamics

- 👉 github.com/muckypaws/PuzzleSolvers

If you enjoy puzzles, retro programming, or watching logic unfold in real time through code, you’re in the right place.

Adventures in ASCII: Animating a 200-Year-Old Puzzle

As the painkillers took hold and I managed a brief nap one afternoon, my brain — ever the rebel — decided to ditch rest in favour of puzzles.

I found myself thinking about the age-old Knight’s Tour problem:

Can a knight move across a chessboard, visiting every square exactly once without repeating?

Given how long the puzzle has existed — and the astronomical number of possible move combinations — there had to be a smarter way to solve it. Surely this wasn’t something that still needed brute force in 2025?

Before diving into code, I paused to appreciate the puzzle’s deep history. The Knight’s Tour has fascinated mathematicians for centuries. One of the earliest known references dates back to the 9th century in an Arabic manuscript by al-Adli, who described a knight’s tour on a 10×10 board. The problem later gained prominence in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries, especially through work by Euler, who in 1759 studied the tour as a graph-theory challenge long before graph theory formally existed. His influence is especially notable given his foundational work in mathematics, much of which still underpins modern cryptography today. The puzzle’s mix of elegance, constraint, and mathematical depth has kept it alive for over a millennium.

From Thought to Terminal

I started by building a basic Python program that could find and display a solution — just something quick to verify whether a path existed, and at that point, I hadn’t yet imagined how much fun it would become blending a logic puzzle with ASCII-based animation and a retro nod to terminal graphics.

def warnsdorff_tour(x, y):

board = [[-1 for _ in range(BOARD_SIZE)] for _ in range(BOARD_SIZE)]

board[y][x] = 0

pos = (x, y)

for move in range(1, BOARD_SIZE * BOARD_SIZE):

x, y = pos

next_moves = []

for dx, dy in MOVES:

nx, ny = x + dx, y + dy

if is_valid(nx, ny, board):

onward = count_onward_moves(nx, ny, board)

next_moves.append((onward, nx, ny))

if not next_moves:

return None

_, nx, ny = min(next_moves)

board[ny][nx] = move

pos = (nx, ny)

return board

Why Warnsdorff’s Rule as the starting point?

It’s one of the most well-known and efficient heuristics for this problem. Unlike brute-force solutions, which try all possible combinations (and there are over 33 million open tours!), Warnsdorff’s Rule uses a simple guiding principle: always move the knight to the square with the fewest onward options. That makes it fast — often producing a solution in milliseconds — and elegant in its simplicity. For someone revisiting the problem after decades away from chess puzzles, it was a clean place to begin: minimal code, immediate results, and a well-documented historical basis. — just something quick to verify whether a path existed.

Once that worked, I added a validation layer to ensure each solution was correct: was every square touched once? Were all knight moves legal? No assumptions. Trust, but verify — a phrase that’s stuck with me since working on early security projects.

With validation in place, I reformatted the output into a clean ASCII-rendered chessboard, labelling each move number from 00 to 63. This alone made the knight’s journey traceable and satisfying to watch.

But then I thought: Why just print the board when you can watch it unfold?

So I brought the knight to life. Using only ASCII in a terminal — just like I used to on systems using a CPX-16 terminal back in the day — the knight began hopping across the board, animated square by square in real-time.

Not a GUI. No frills. Just code and characters solving a centuries-old puzzle with a touch of retro charm.

But I wasn’t done yet.

What if not all starting positions worked? What if the algorithm failed under certain conditions — or worse, silently produced invalid results?

I dug deeper… and discovered exactly where the knight might get stuck.

How the Algorithm Works

The first solution used Warnsdorff’s Rule — a fast and elegant heuristic dating back to the 19th century. The idea is simple: at each step, move the knight to the square with the fewest onward options. The fewer paths a square offers, the more likely it is to become a dead end — so the algorithm visits those first.

Why choose Warnsdorff’s Rule? It remains one of the most efficient and time-tested methods for solving the Knight’s Tour. Unlike brute-force approaches, which are computationally heavy and impractical on anything but the smallest boards, this heuristic is light, fast, and remarkably effective. On an 8×8 board, it often produces a complete tour in milliseconds — no recursion, no backtracking, just greedy logic and a dash of foresight.

For a project that started as a nostalgic return to puzzles, it was the perfect fit: clean, performant, and rooted in mathematical history.

To increase reliability, I later added a fallback: a slower, recursive backtracking algorithm that kicks in if Warnsdorff’s heuristic fails. This hybrid approach offers the best of both worlds — speed where possible, thoroughness where necessary. Sometimes, the most enduring solutions are the ones refined over time rather than reinvented from scratch.

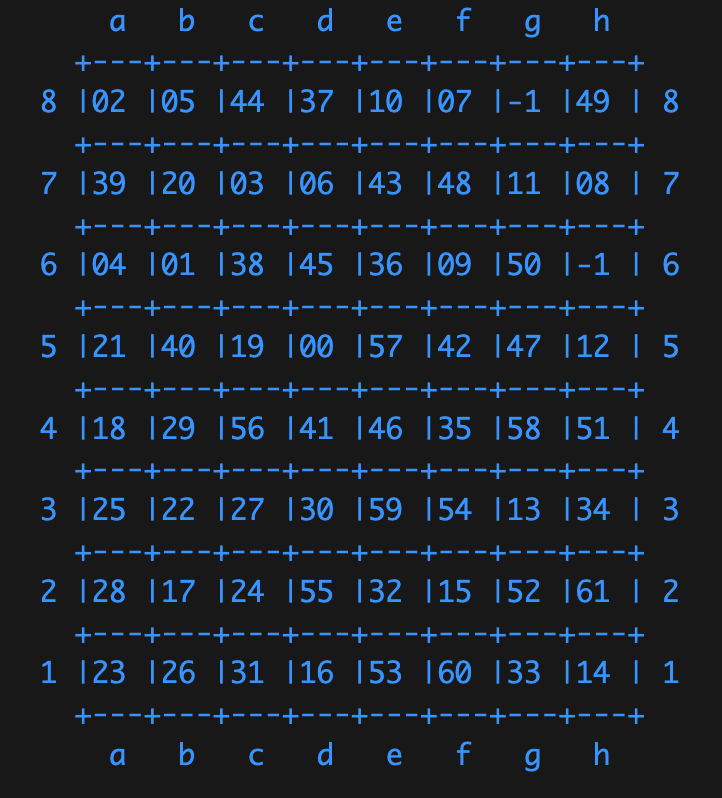

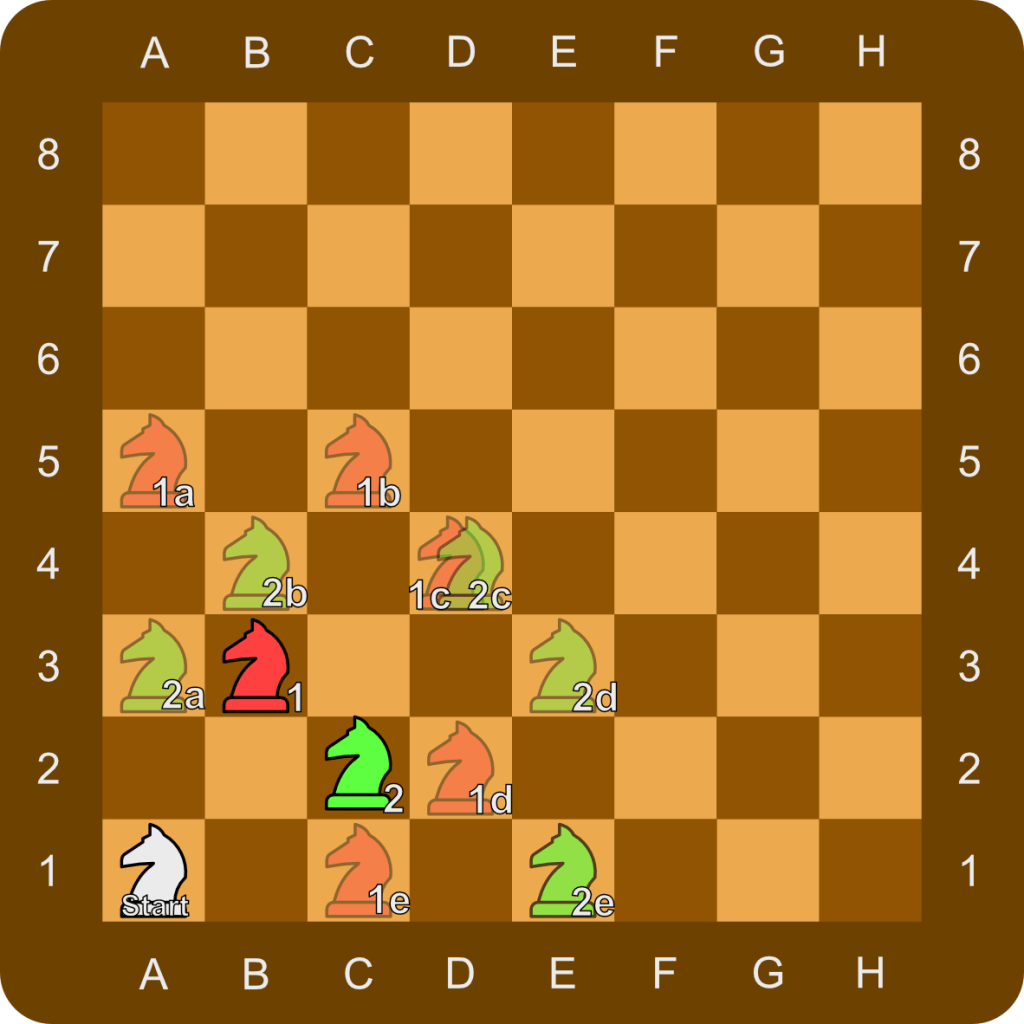

Let’s take an easy example. Our knight starts at A1. From here, there are only two valid moves (B3 and C2), which I’ve highlighted in red and green.

The heuristic evaluates the number of forward moves available from each valid next position.

- Green (C2) can move to A3, B4, D4, E3, and E1 — also not back to A1.

- Red (B3) can move to A5, C5, D4, D2, and C1 — but not back to A1 (already visited).

Below is an animated image showing the next move and evaluated forward moves from the next position.

But it’s not perfect.

During testing, I found starting positions like d8, g7, and d5 that consistently led the knight into dead ends. No warning, no error — just a half-finished board and a knight with nowhere left to go.

The ASCII Grid shows the moves calculated from D5 = 00, next move B6 = 01, A8 = 02 etc… follow the index number inside the grid to see the moves selected…

This raised an important question: Was it the algorithm that failed, or my implementation of it?

After reviewing the logic carefully and comparing results, it became clear that the algorithm was behaving as designed. Warnsdorff’s Rule is a heuristic — not a guaranteed solver. It makes locally optimal decisions without looking ahead. That means, depending on how ties are broken (when multiple moves have the same onward count), it can still paint the knight into a corner. So technically, the implementation was correct — it’s just that the heuristic isn’t infallible.

In the original implementation

def warnsdorff_tour(x, y):

board = [[-1 for _ in range(BOARD_SIZE)] for _ in range(BOARD_SIZE)]

board[y][x] = 0

pos = (x, y)

for move in range(1, BOARD_SIZE * BOARD_SIZE):

x, y = pos

next_moves = []

for dx, dy in MOVES:

nx, ny = x + dx, y + dy

if is_valid(nx, ny, board):

onward = count_onward_moves(nx, ny, board)

next_moves.append((onward, nx, ny))

if not next_moves:

return None

_, nx, ny = min(next_moves)

board[ny][nx] = move

pos = (nx, ny)

return board

The line highlighted

_, nx, ny = min(next_moves)

Simply selects from the list of valid moves, the first in the list of minimum moves. Therefore when

next_moves =

0 = (3, 4, 7)

1 = (3, 0, 5)

2 = (6, 3, 4)

3 = (7, 4, 5)

len() = 4

Both index 0 and 1 have the lowest onward count of 3. But min(next_moves) doesn’t just consider the first value — it compares the full tuple. So (3, 0, 5) is chosen over (3, 4, 7) because 0 < 4.

This behaviour isn’t faulty, but it creates a hidden bias: the knight’s movement is now influenced by the spatial coordinates, not just onward count. That might sound fair — until you realise it consistently prefers certain directions due to the way (x, y) values are ordered.

The real twist came when I realised that some of the failure cases — like d5 — occurred when the knight started near the centre of the board, where it typically has access to the full set of 8 possible moves. In these positions, many candidate moves often have identical onward counts, making tie-breaking especially important. Other failures, like g7, occur near the edge, but still involve multiple equal onward options where the bias in implementation becomes apparent. That’s where a subtle directional preference sneaks in.

Most implementations (including mine at first) define the knight’s moves in a fixed order. So when multiple moves have equal onward counts, the algorithm chooses the first one in the list. This means the knight develops an unconscious “directional bias” — always favouring certain paths first. On a central square, this bias can send the knight down a doomed path, even though other equal-looking options might have worked fine.

Why not check the theory yourself… place the Knight on the board at D5, you can see the next move allows all eight legal moves for the knight…

To counter this, some implementations shuffle equally-ranked moves to add variation, or introduce secondary tie-breakers based on board geometry (like distance from the centre or board edges). Others go further and use limited lookahead to test the next few steps. But even then, the heuristic remains greedy — not infallible. Greedy, in this context, means the algorithm always chooses the move that looks best at the current step, without considering the long-term consequences. It doesn’t explore alternate paths or backtrack; it simply hopes that a series of short-term decisions will result in a full solution. That works surprisingly often — but not always.

In fact, if you run different implementations of Warnsdorff’s Rule — with or without randomness, tie-breaking, or sorting — you may see different start positions fail, depending on how the choices unfold.

So I added a fallback.

If Warnsdorff’s heuristic fails, the program switches to a slower, recursive backtracking method. It guarantees a solution from any valid starting square, at the cost of performance.

def backtrack_tour(x, y):

board = [[-1 for _ in range(BOARD_SIZE)] for _ in range(BOARD_SIZE)]

board[y][x] = 0

solutions = []

def dfs(cx, cy, move):

if move == BOARD_SIZE * BOARD_SIZE:

return True

next_moves = []

for dx, dy in MOVES:

nx, ny = cx + dx, cy + dy

if is_valid(nx, ny, board):

next_moves.append((nx, ny))

# Optionally sort for Warnsdorff-style guidance

next_moves.sort(key=lambda pos: count_onward_moves(pos[0], pos[1], board))

for nx, ny in next_moves:

board[ny][nx] = move

if dfs(nx, ny, move + 1):

return True

board[ny][nx] = -1

return False

if dfs(x, y, 1):

return board

return None

With this hybrid approach, the knight now completes its tour from any starting position — fast where it can be, thorough when it needs to be.

And best of all? Every solution is validated before it’s displayed or animated.

Trust, but verify.

Even code makes mistakes. That’s why I added a validation step: to confirm that every square is visited exactly once, and every move follows the knight’s L-shaped pattern. It’s not just a safety net — it’s peace of mind, especially when heuristics are involved.

def validate_tour(board, verbose=True):

positions = [None] * (BOARD_SIZE * BOARD_SIZE)

for y in range(BOARD_SIZE):

for x in range(BOARD_SIZE):

move = board[y][x]

if not (0 <= move < BOARD_SIZE * BOARD_SIZE):

if verbose:

print(f"Invalid move number {move} at ({x}, {y})")

return False

if positions[move] is not None:

if verbose:

print(f"Duplicate move number {move} found")

return False

positions[move] = (x, y)

for i in range(1, BOARD_SIZE * BOARD_SIZE):

x1, y1 = positions[i - 1]

x2, y2 = positions[i]

dx, dy = abs(x1 - x2), abs(y1 - y2)

if not ((dx == 1 and dy == 2) or (dx == 2 and dy == 1)):

if verbose:

print(f"Invalid knight move from {positions[i - 1]} to {positions[i]}")

return False

if verbose:

print("✅ Tour is valid.")

return True

Terminal Animation

Once the solver and validation were working, the next step was to make it visual. I didn’t want just numbers on a static board — I wanted to see the knight move.

Not in a web browser. Not with Pygame. Just the terminal. Old school.

Using basic ASCII characters, I animated the knight’s tour square by square. Each move is shown step by step, updating the board in real time. The knight’s current position is marked with a special symbol (🐴 or K), and previously visited squares are labelled with their move numbers.

This wasn’t just eye candy — it became a powerful way to trace logic. Seeing the knight hop and weave across the board made it easier to spot patterns, recognise symmetry, and even question the logic of certain failed paths.

It also added something else: personality. There’s something inherently satisfying about watching logic unfold as movement — almost like watching code dance.

It reminded me of early experiments on monochrome screens, where every animation felt magical because we made it happen with code, not layers of abstraction.

Visualising and Explaining Failure

Once I started spotting failed tours from specific starting positions, I knew I needed more than just console output to understand why. It wasn’t enough to say “Warnsdorff’s Rule failed here” — I wanted to see why it failed.

These failures weren’t dramatic. The knight simply… stopped. The board would freeze after a number of successful moves, with no legal options left. Watching the animation in real time helped — but I wanted to go further.

This is where diagrams came in.

By overlaying the board with heatmaps of onward move counts, or drawing arrows to trace the knight’s path from a failed run, patterns began to emerge. I could see how early decisions — especially when faced with equally weighted options — sometimes led to boxed-in corners and unreachable areas. The algorithm had essentially sealed off parts of the board behind itself. This helped explain why central start positions like d5 failed more often: too many tempting options, and no ability to look ahead at long-term consequences.

In future iterations, I plan to build out richer visual overlays and possibly even an interactive web-based demo. But even a few carefully chosen stills have been enough to reveal where the logic falters.

As satisfying as it is to see a knight complete the tour, there’s a surprising beauty in watching it fail — because failure, when understood visually, becomes a tool for refinement.

Future Visuals and Heatmaps

To explore this further, I’m experimenting with ASCII heatmaps. Imagine a chessboard printed with numbers instead of pieces, where each square shows how many onward moves were available when the knight landed there. Or a live-updating board where shading intensity reflects constraint pressure. Even without full graphics, these views can help visualise tour efficiency and highlight problem zones — all while keeping things textual, lightweight, and terminal-friendly.

If you’d like to explore the code or try it yourself, you can find everything in the public repo: 👉 github.com/muckypaws/PuzzleSolvers

Final Thoughts

The Knight’s Tour may be centuries old, but it still has lessons to teach — not just about chess, but about algorithms, heuristics, and how we reason through complexity. What started as a nostalgic puzzle turned into a personal project filled with animation, analysis, and just the right amount of head-scratching.

Whether you’re exploring pathfinding, visualising logic, or just love watching code come to life in unexpected ways — I hope this journey gave you something to think about.

If you do take it further, I’d love to see what you discover. Maybe your knight will find a path mine didn’t.