Knee Deep: My 2025 NHS Surgery Story

TL;DR

In May 2025, I returned to the NHS for my second knee replacement, expecting lessons to have been learned since my first in 2017. Instead, I found history repeating — inadequate pain relief, fractured communication, and a system more defensive and disjointed than ever. This is a personal account, but also a reflection on what happens when the healthcare system prioritises paperwork over people.

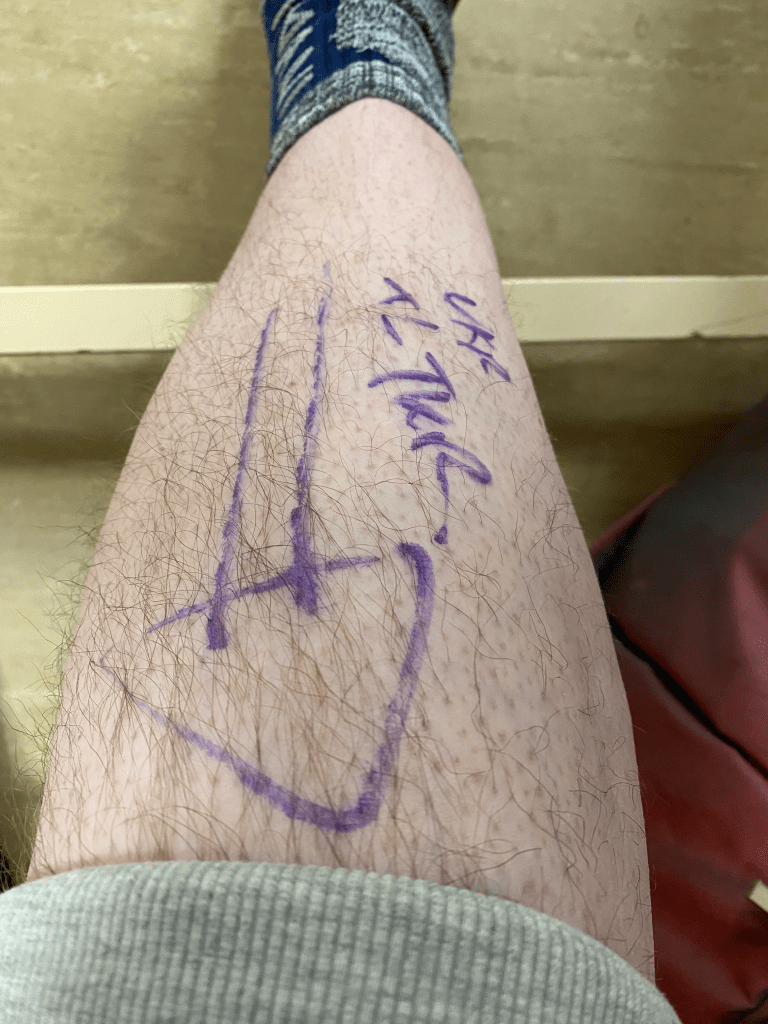

Prologue: The Long Road to the Operating Table

In 2007, during the innocent chaos of moving house, I felt a searing pain in both knees. The GP at the time dismissed it as overexertion. Eventually, I went private and received an MRI. Diagnosis: osteoarthritis in both knees. Bone on bone. No cartilage. The cause of my pain laid bare.

But I was “too young” for a knee replacement. I was told that replacements last around 10 years and that if I needed more later, fusion would be the only option. So began years of slow physical decline: less mobility, more pain, less exercise, weight gain. A downward spiral.

Despite clear MRI evidence and worsening symptoms, the NHS insisted it could be resolved with physiotherapy. That’s right—bone on bone, and the official remedy was stretches and resistance bands. 🙄

Funding for my first knee replacement was eventually approved in 2016, but surgery didn’t take place until 2017. Even then, it wasn’t without resistance or delay. The wheels turned slowly, even as my body protested loudly.

In 2017, against all odds, my first knee replacement was scheduled. Complications followed. A torn ankle sheath led to a second surgery. Then in 2019, sepsis almost killed me. Emergency surgery saved me, but left me with chronic conditions, PoTS, anaemia, more surgical interventions than I can count, and the kind of bodily scars you’d expect to see on a Roman gladiator.

As the years passed. Pain remained and intensified. And now, in 2025, I was finally scheduled for my second knee replacement.

Arrival: The Day Surgery Surprise

7am check-in. No food, minimal water. The location had changed since 2017—now a day surgery unit. My stomach sank when I was told I’d likely be discharged same day.

Last time I had a knee replacement, I was in for two weeks. I froze for a moment — fear, disbelief, and a creeping sense of resignation washed over me.

I knew what was coming… The thought of enduring all that pain, all that recovery, alone at home within hours of surgery was overwhelming. I didn’t shout or protest — I just… panicked quietly, the kind that stays under your skin and eats away at your confidence.

A nurse recognised me from years ago. She’d once visited me at home during my first knee replacement recovery, yet now avoided eye contact. Something had changed.

The anaesthetist arrived, brisk and businesslike. She immediately began pushing hard for a spinal block. I explained — calmly but firmly — that it wasn’t an option. In 2017, they’d tried it, and I hadn’t even been able to tolerate the initial numbing injection before the main spinal needle.

I reminded her that the head of her own department had assessed me back then and left a note on my file explicitly stating that spinal wasn’t suitable in my case. Still, she pressed on — insisting spinal would reduce post-op pain and speed up recovery.

I stuck to my decision. I wasn’t trying to be difficult — I was trying not to relive a traumatic experience. She looked less than pleased. And as I sat there, jaw clenched, I remember thinking: “The surgeon isn’t going to use a softer mallet or drill depending on my anaesthetic.” Of course, I didn’t dare say that out loud.

Eventually, and with obvious reluctance, she agreed to proceed with general anaesthetic (GA).

Going Under (Sort Of)

Unlike previous surgeries, this was the first time I didn’t get the dreamy descent from ten — no “you’ll feel a little sleepy now.” Just a blur — a transition from fluorescent lights and tension to something far more primal.

I came to in recovery, not slowly, but violently — my eyes wide, my body locked in agony, and the sound of my own voice screaming into the void. I remember looking down, confused, trying to make sense of where I was, what had happened, and why everything hurt so much.

A nurse appeared in my line of sight, pushing fentanyl into my hand cannula. More followed. It wasn’t touching the pain. I begged to be put back under. I didn’t want relief — I wanted escape.

I remember thinking: “Fentanyl? Isn’t that something we hear about in American overdose documentaries?” I didn’t even realise it was used here in the UK. But here it was — American pharmacy in action — and still, the pain broke through.

“You shouldn’t be feeling this,” someone said. That line again — the subtle accusation that I was exaggerating.

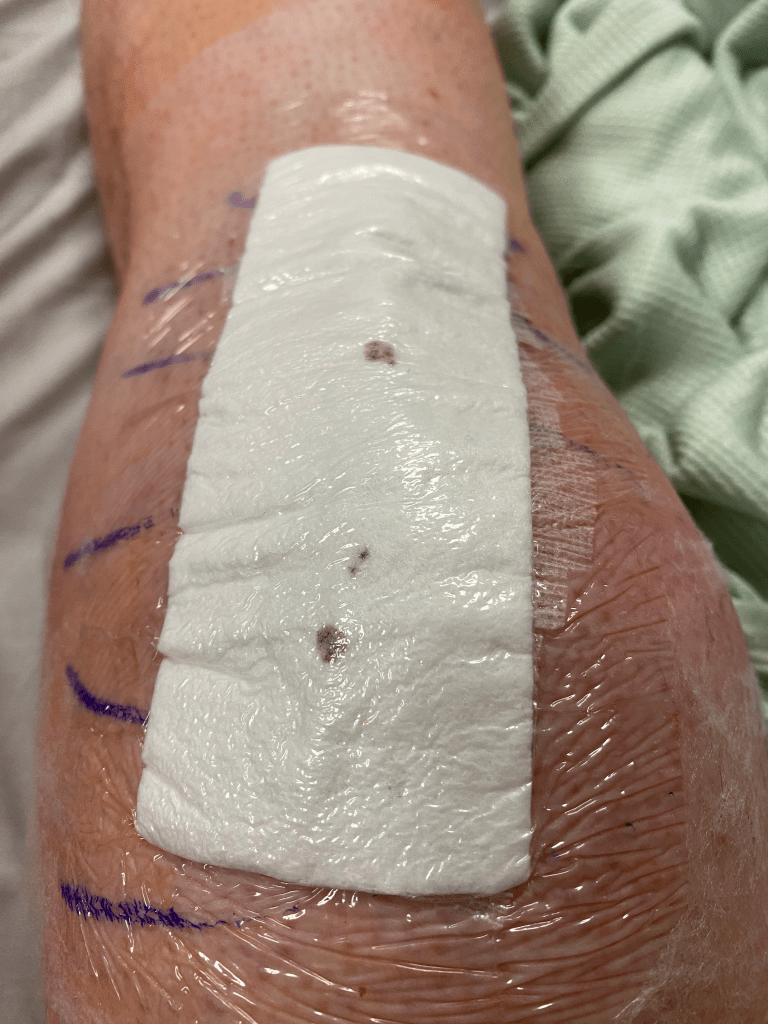

Eventually, I was told I’d go to X-ray to check the joint and then be moved to the ward. I think I drifted again after that.

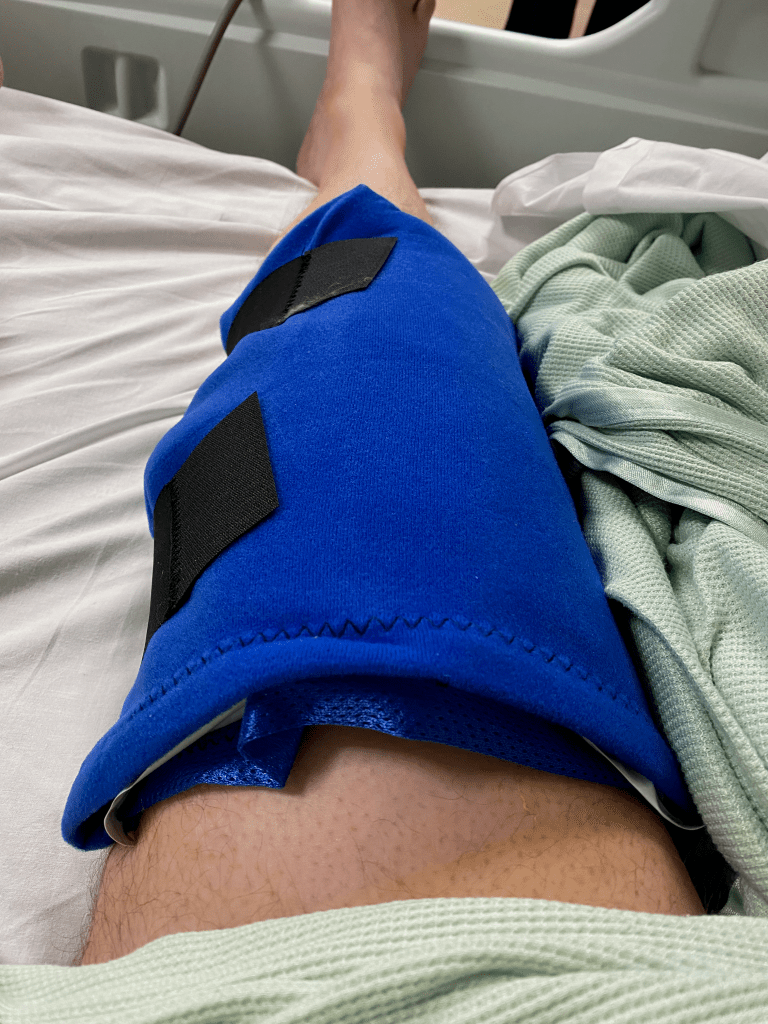

When I came round again, I was on the ward — foggy, nauseous, and already regretting everything. No PCA this time — no patient-controlled morphine drip like I’d had before. Just a single, small dose of oral morphine. Not much comfort. Not much control.

I lay there, trying not to cry. Not from the pain alone, but from the creeping sense that this experience was already spiralling out of my hands.

The Toe-Wiggling Olympics

Later that evening, a physio arrived — upbeat, clipboard in hand. His goal was to get me on my feet. He asked me to wiggle my toes… nothing. Then he placed his hand on my feet and asked if I could feel his touch… still nothing… only pain…

He returned around 8pm, expecting progress. Still surprised. Still hopeful. But there was zero sensation in my feet.

Meanwhile, one of my regular diabetic medications had been withheld without explanation. By the next morning, my blood sugar had spiked to over 15 mmol/L. It wasn’t until the drug was reinstated — two days later — that my levels returned to normal. A predictable result, yet apparently a surprise to those overseeing my care, especially given I hadn’t eaten anything since Wednesday.

The Night Shift: Pain is a Paperwork Issue

Around 3am, the pain was unbearable. I hadn’t slept — every adjustment sent sharp jolts through my knee. I called out, asking for more pain relief. The response was clinical and dismissive: “You’ve already had something.”

They offered IV paracetamol. The cannula stung as soon as the flush began — a clear sign it wasn’t in properly. I told them. I was told it was in my head.

I’ve had more cannulas than I can count. I know the difference between a sting and a backflow. Still, they insisted. It took another round of negotiations — not requests, negotiations — before someone finally agreed to try a new line.

Eventually, a new cannula was placed in my arm. What was left of the IV paracetamol went in. The pain stayed. I lay awake, exhausted and hollowed out.

At 6am, I was finally given a single codeine tablet. Just one. Less than I take at home for a mild flare-up. I didn’t feel cared for — I felt rationed. Punished, maybe. Any clinical sense of judgement felt entirely absent.

Friday: One Step Forward, Two Steps Questioned

Later that morning, a doctor finally made his way to my bedside. I explained how much pain I’d been in overnight and that I was still struggling. He looked surprised — not dismissive, just genuinely puzzled at how little had been prescribed. When I explained that at home, I only take two co-codamol tablets when necessary, he nodded in agreement. He recommended oral morphine every three hours and ensured it was now correctly written up. A dose was finally given.

But while the prescription was written, access to pain relief remained disjointed. Despite the doctor’s explicit instructions — codeine and paracetamol every 4–6 hours, oral morphine every three — the nurses continued to gatekeep according to the regime they felt appropriate. Doses were inconsistent. Requests were deflected. Pain relief became a negotiation. It remained erratic.

Later that day, a physio appeared — someone I recognised from my 2017 knee replacement. We exchanged a few pleasantries. Friendly but formal. I sensed something was being held back. She had me get out of bed using a zimmer frame and shuffle a short distance across the ward. That brief shuffle would be the measure of whether I was “discharge material.” She said she’d return later to try the stairs. I nodded, but I was panicking.

Pain levels were still high, and I was moving more from will than from strength. By afternoon, she returned and reassessed. I wasn’t ready. She said someone else would check stairs with me in the morning.

At this point, I still hadn’t eaten anything solid. There had been no routine for washing or personal care. The basics I remembered from 2017 just weren’t offered. I was invisible, but also — apparently — nearly ready for discharge.

Saturday: Stair Trials and Red Flags

The physio from Thursday returned — but his demeanour had changed. No more small talk, no warmth. It felt like something had shifted behind the scenes — as if a note had been added to my file and now I was being handled rather than helped.

This time, he insisted on crutches instead of the zimmer frame. We went for a slow, painful shuffle before he announced we were going to try the stairs. My stomach sank.

The stairs were a good distance away. He fetched a wheelchair, but didn’t factor in the challenge of transporting someone tall with a leg that couldn’t bend. I’m 6’5″, and post-op my knee wouldn’t flex enough to rest comfortably on the footplate. He looked irritated by this — as if it was a personal inconvenience — but eventually found an insert to support my outstretched leg.

By the time we reached the stairs, I was in significant pain and trying to hide the rising panic.

I made one failed attempt after another. Each time, the pain intensified until I was shaking and physically drained. Eventually, the physio wheeled me back and insisted I take my full dose of pain relief.

Back in bed, I was left to stew in the knowledge that the only thing keeping me in hospital at this point was my failure to climb those stairs. Not recovery. Not readiness. Just stairs.

Worse still, I was still unsure how I’d be getting home. I’d filled out paperwork in advance, provided photographs, flagged mobility issues — and no one had looked. Every question about transport or discharge planning was passed in circles. The staff hadn’t read a thing. The entire day felt like I was being tested, not treated.

Friends visited in the afternoon. Nurses wrongly assumed they were my lift. I panicked and my anxiety went into overdrive when they asked questions I couldn’t answer within earshot. “I don’t feel safe,” I told them. That was the truth.

Sunday: The Discharge Gauntlet

Sunday morning, on painkillers strong enough to power a Tesla, I managed the stairs. Success meant one thing: get him out.

Shortly after, a healthcare assistant arrived to take my blood pressure. It had been monitored routinely throughout my stay, but this time they wanted a lying-to-standing test. I thought to myself: this should be interesting with my PoTS…

Sure enough, on standing, my blood pressure dropped to 86/64. The HCA looked concerned. But instead of correctly recording it, she said, “Let’s wait a few minutes and try again.” Any PoTS patient could have told you that standing longer makes the response worse — heart rate climbs. She repeated the test until she had a reading she was happy to record.

Why? The same hospital diagnosed me. I had declared my PoTS. It was on file. Was this about ticking a box to meet discharge criteria? Is it better to record a convenient number than an accurate one?

I overheard my case being discussed. I popped my head up to help. The doctor scolded me publicly: “I could be talking about any patient.” A nurse muttered: “He’s the only one with a knee replacement, and we are talking about him.”

I asked to check the discharge meds that arrived. They refused at first, stating that’s for discharge shortly. I remember in 2017 they made a mistake and left meds out, hence I wanted to know what I was in for… Eventually, I saw: blood thinners, laxatives, a tiny pack of codeine, that’s all…

I explained that the physio that morning had monitored my pain and said I’d need oral morphine for the first few days at home.

“Not our problem,” I was told. “No doctor available. Pharmacy closed.”

That was it. No apology. No workaround. No empathy.

A critical part of my care had just… timed out.

Going Home Without a Plan

The ward sister who earlier promised to organise and book transport earlier in the day shrugged. “Get a taxi.” She said she had. But she hadn’t. Nothing was booked — despite what was discussed, agreed, and promised.

Another patient — bless him — spoke up for me. “He clearly can’t get into a car.”

Given I was left with trying to find a people carrier taxi or something I could get into, I realised there’s no way I could get my clothes bag, and equipment/mobility aids home on my own. It’s a struggle to balance on crutches, let alone carry anything heavy… impossible…

I called my friends again. They kindly agreed to come and collect my belongings.

Again the ward sister assumed they were here to collect me, the same ward sister the day before I explained they owned a mini, and there’s no way I can get into that vehicle in my current state… it was a struggle getting in before surgery…

The ward sister huffed and muttered about needing the bed for the next intake. There was no sense of transition, only removal.

I made an emergency post on social media for anyone nearby with a van or people carrier to help get me home. Someone I thought was out of the country messaged to say they were on their way!

When they arrived to collect me, The ward-sister lied to my friends, saying she’d have to cancel patient transport now. (The one she promised to sort in the morning, only to find out she didn’t and told me to find my own way). I told them plainly: “I didn’t feel safe here.” She didn’t appreciate that honesty.

Eventually, friends with a van arrived and got me home — a painful, awkward journey followed by external steps with no grab rails, no support, and no clue how I’d manage once the door closed behind me.

Inside, the reality hit harder than expected.

There was no care package. No instructions. No call. No follow-up. Just me, crutches, and a bag of blood thinners and laxatives.

No real medication. No plan. No dignity.

It echoed what happened during my first knee replacement in 2017 — the same failure to ensure appropriate pain relief upon discharge. I even wrote about that in a piece titled [Caffeine and Codeine] – https://muckypaws.com/2017/12/03/caffeine-and-codeine/, never expecting history to repeat so precisely eight years later.

Monday: The Phone Calls Begin

Monday came, and I still had no effective pain relief. The hospital had discharged me with codeine only — no oral morphine, despite what had been discussed.

The physio called for a home visit. He was polite, but clearly uninformed. He didn’t know about the pain situation. When he arrived, I explained everything — the missing medication, the agony of trying to manage stairs, and the complete absence of follow-up support. He seemed surprised and quietly frustrated.

I then called the surgeon’s secretary, who told me it was now a GP issue.

I called the GP practice. They were overwhelmed, short-staffed, and unable to help. I was told to call 111.

111 said there were no prescribers available until after 6:30pm, and that I should call back then. When I did, I had to repeat the entire story — again — because my earlier case had been closed. “It makes our stats look bad…” they explained.

Eventually, a GP issued a small prescription, which a friend kindly collected.

That night, finally, I was able to ascend the stairs to head to bed… I didn’t sleep well… the pain intensifies at night… waking every half hour or so… eventually I saw dawn rise, a red sky through the trees from my bedroom windows, thinking … I don’t know how I’m going to get down those stairs…

Day 4: This Pain Is Not The End

I’ve been trying to ration the oralmorph — saving it for nights, just to get up and down the stairs, or to claw back a few hours of broken sleep. During the day, it’s codeine only.

But the pain is relentless. It sharpens in the evenings and becomes unbearable once I lie down. There’s no real way to get comfortable. Even when I manage to fall asleep, I wake within the hour — pain stabbing through the haze, forcing me to shift, adjust, breathe through it, and hope for another fragment of rest.

Yesterday, the nausea returned. I spent the afternoon light-headed and unsettled. Overnight, I soaked the bed in sweat — clothes, sheets, pillow. Could it be infection? The medication? Or just the accumulated toll of everything my body’s been through?

The hardest part? I’m not even sure what normal is supposed to feel like anymore.

Final Thoughts

This wasn’t just a surgery. This was a case study in how the system fails by design.

Yes — the NHS is under enormous pressure. I don’t expect room service or spa-level care. I know beds are in demand and recovery at home is the end goal. But this wasn’t about luxuries — it was about safety, dignity, and the absence of joined-up care.

Over the years, I’ve raised concerns. I’ve been told lessons were learned. But in 2025, I experienced the same failings that occurred in 2017. Communication between teams is still fractured, with clear lines of demarcation — surgeons slice and dice, nurses handle the ward, and pain control falls somewhere between the gaps.

Everyone stays in their lane. No one leads. And the patient gets lost in the handovers.

- Pain relief is treated as optional — prescribed by doctors, then quietly withheld or rationed by others

- Communication is fragmented, with no ownership from anyone — just circular deflections

- Discharge is about freeing a bed, not about ensuring recovery or dignity

I came in with hope, experience, and detailed preparation. I left exhausted, under-medicated, and disillusioned.

This wasn’t the story of a difficult patient. This was the story of a system that’s become defensive, procedural, and unable to admit when it isn’t coping.

And me? I’m still here — trying to recover, to rest, to reset — while quietly asking: if this is what it’s like for someone who knows how to advocate for themselves… what happens to those who don’t?

I didn’t expect miracles. But I didn’t expect to feel so disposable.

Maybe that’s the story here.

Join the Discussion

Have you experienced similar challenges with NHS care, hospital discharge, or recovery support? Do you work in the system and want to share your perspective?

I’d love to hear your thoughts — drop a comment, share your story, or get in touch via the blog. Let’s talk about how we make this better for everyone.