How Protecting Children Online Created a Privacy Nightmare for Everyone

TL;DR

The UK’s Online Safety Act forces millions of adults to hand over passport photos and selfies to private companies just to access games, social media, and online communities. These companies have poor security records, store data longer than promised, and often transfer your identity documents overseas without proper legal safeguards. Recent breaches (like the TEA app exposing 72,000 photos in July 2025) prove this creates “honeypots” for hackers rather than protecting children. Meanwhile, tech-savvy kids are already bypassing these checks with VPNs and fake documents. The government could solve this with a simple token system like the DVLA share-codes, but refuses to admit their approach is fundamentally flawed. Bottom line: this law creates more privacy risks than it prevents.

A template letter has been made available to write to your MP in respect to these concerns, and available for download here :

Prefer to listen?

Alternatively, Key points in video form courtesy of NotebookLM’s new feature.

When Home Was Still a Safe Haven

By now, most of us feel like we’ve heard everything about the Online Safety Act. The headlines fixate on adult content, but the reality is far broader. This law reaches into gaming, streaming, and everyday online communities.

When I was growing up, bullying ended when you reached home, your little piece of sanctuary. Today, the always-connected world follows children into their bedrooms. Devices, apps, and messaging platforms blur the lines between schoolyard taunts and home life.

Years ago, I worked on a child online safety initiative with an extraordinary colleague from Mexico. Her perspective shocked me: in her community, people feared being physically kidnapped more than having their bank details stolen. It drove home how “safety” means very different things depending on where you live.

We built age-group-specific training for parents, teachers, and children to supplement CEOP’s (Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre, now operating as the CEOP Command within the UK’s National Crime Agency (NCA) efforts. https://www.ceop.police.uk/safety-centre

While CEOP teams delivered excellent presentations to schools, teachers often felt overwhelmed and under-supported afterward, facing vast knowledge gaps with little ongoing help. Our initiative aimed to fill those gaps with practical, hands-on training.

Back then, parents were stunned to learn that photos they’d shared on social media contained GPS metadata that could reveal their location. Teens who thought they “knew it all” quickly changed their tune after watching a live penetration-testing demo on one of their own accounts. Teachers shared stories of parents undermining safety efforts, one parent even gave their six-year-old a phone with explicit images as a “joke.”

I learned back then, different countries approached the problem with varying intensity. Singapore taught online safety from the earliest years. The US was hit-and-miss depending on the state. The UK and Europe had some strong initiatives, but gaps remained.

The Education Gap We’re Ignoring

Before we rush to implement sweeping identity verification, perhaps we should ask a more fundamental question: why are we handing smartphones and social media accounts to children who aren’t developmentally ready for them?

I’ve witnessed parents create Facebook accounts for eight-year-olds, driven by fear of missing out rather than any genuine need. The same parents who wouldn’t let their child walk alone to the corner shop will hand them unfettered access to the entire internet. We’ve normalized giving children powerful communication tools without teaching them, or their parents, how to use them safely.

The real problem isn’t inadequate age verification; it’s inadequate education. Many adults who didn’t grow up with technology feel completely overwhelmed by its complexity. How can we expect them to guide children through digital literacy when they’re struggling to understand it themselves? Teachers report feeling under-supported after brief CEOP presentations, left with vast knowledge gaps and little ongoing help.

What we need are sustained, government-backed education campaigns, not just for children, but for parents, teachers, and adults. Regular awareness programs that demystify technology, explain privacy settings, and teach families how to have meaningful conversations about online safety. Instead, the Online Safety Act skips this hard work entirely, opting for the technical quick-fix of identity verification that creates new problems while ignoring the root causes.

Teaching digital citizenship should start before children get their first device. Parents should understand what they’re signing their family up for when they create social media accounts. Adults should feel confident enough to set boundaries and have informed discussions rather than throwing up their hands and hoping technology will solve it for them.

Inconsistent Safety Rules Closer to Home

The fragmentation plaguing digital safety becomes starkly apparent when we examine England’s own backyard. More than a decade after concerns first emerged about teacher-student social media boundaries, England still operates without national standards. Schools continue making ad-hoc decisions about whether staff can friend pupils on Facebook, connect with parents on Instagram, or add students on Snapchat.

The UK Safer Internet Centre confirms that “different education settings have different policies around this so it varies depending on where you work.” Meanwhile, the Teaching Regulation Agency regularly investigates teachers for alleged social media misconduct, creating a peculiar situation where educators face professional sanctions under guidelines that don’t formally exist.

The contrast with neighbouring regions is telling. Wales established formal regulator guidance on teacher social media use back in 2016, setting clear expectations for professional conduct online. England? Still waiting.

The Department for Education’s social media guidance page remains unchanged since 2014.

The result is a postcode lottery of professional standards. Rural schools often permit teacher-parent connections that formed before enrollment, while urban institutions typically ban all personal contact. Staff navigate this uncertainty while knowing that a single misinterpreted post could trigger a professional investigation.

This domestic inconsistency reveals a fundamental flaw in how the UK approaches digital safety: if we can’t establish consistent rules for teacher-student interactions after a decade of trying, how can we expect the Online Safety Act’s sweeping requirements to succeed when layered onto this already fragmented foundation? The result risks generating more confusion than clarity for those tasked with keeping children safe online.

The Act in Context

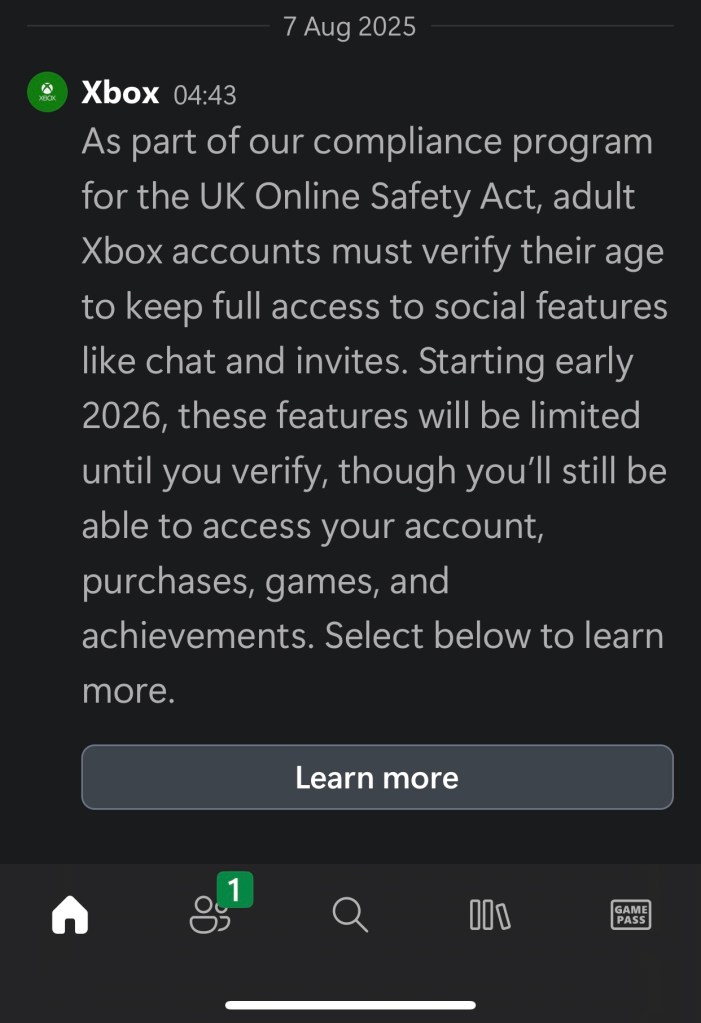

From 25 July 2025, Ofcom began enforcing the law’s child safety obligations. Services likely to be accessed by children must conduct risk assessments and implement “highly effective” age-assurance. This isn’t just adult sites: gaming networks, forums, music, and social platforms are all in scope. Xbox, for example, will require a one-time age check for UK accounts to retain full social functionality from early 2026.

Ofcom’s January 2025 guidance defines “highly effective” as accurate, reliable, robust, and fair. Approved methods include credit card checks, face or ID scanning, and digital identity tools, while self-declaration won’t suffice.

Platforms are responding quickly:

- Xbox: One-time UK age check in 2026 to keep social features.

- Discord: Default blurring of mature content with age verification needed to opt out.

- Spotify: Face-scanning ID checks via Yoti; failed checks may disable accounts.

- Reddit & Bluesky: Using Persona and Kids Web Services for UK verification.

- Others: Grindr, X (Twitter), Nexus Mods, and even Wikipedia are considering or implementing compliance measures.

Pushback is growing. A parliamentary petition to repeal the Act has passed half a million signatures: https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/722903

Critics, including civil liberties groups and tech investors, warn about privacy risks and overreach: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/aug/09/uk-online-safety-act-internet-censorship-world-following-suit

The Government has stated it will not repeal the Act, insisting on Ofcom-led “proportionate” enforcement.

The Privacy and Data Protection Clash

The Online Safety Act does not itself create a lawful mechanism for moving UK identity data overseas. If a provider, or their age-assurance vendor, stores or processes passport scans or biometric data outside the UK, they must still use a lawful transfer mechanism and conduct a documented Transfer Risk Assessment under UK GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation): https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/uk-gdpr-guidance-and-resources/international-transfers/international-data-transfer-agreement-and-guidance/transfer-risk-assessments/

In plain English: most age verification companies can’t legally handle UK data the way they claim.

One legal mechanism is the UK Extension to the EU-US Data Privacy Framework (DPF): https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-us-data-bridge-supporting-documents/uk-us-data-bridge-factsheet-for-uk-organisations

For this to apply, the US recipient must be DPF-certified and explicitly opted in to the UK Extension. You can check which companies are certified here: https://www.dataprivacyframework.gov/list

Some major vendors are on the list (e.g., Stripe; Persona states it is certified), but others are ineligible (e.g., Israeli-based AU10TIX) or silent on their transfer approach, likely relying on Standard Contractual Clauses without publicly available transfer risk assessments.

Only US organisations under FTC or DoT jurisdiction can join the DPF… banks, insurers, and telecoms can’t… which forces many to rely on alternative safeguards.

What this means for you: Companies collecting your passport photos may be breaking data protection law from day one.

Vendor examples:

- AU10TIX: Retains biometric data until verification is complete or up to three years after the last interaction. Processes data in the EU, US, UK, and Israel. Suffered a security lapse where admin credentials were exposed for over a year.

- Yoti: Deletes directly collected data promptly, but partner mobile provider checks can retain records for up to two years.

The risk is clear: without strong oversight and verifiable deletion, “delete after verification” becomes a hollow promise, and cross-border transfers risk bypassing DPF requirements entirely, creating honeypots of sensitive identity data that are irresistible to threat actors.

When “Delete After Verification” Becomes a Dangerous Lie

Why ID data is premium loot. Passport and licence images, selfies, and liveness videos enable account takeover, synthetic identities, SIM-swap fraud, high-value social-engineering, and long-tail stalking/harassment. Unlike a password, you can’t rotate a face or a passport number once it’s leaked.

The human factor trumps security spending. The most common routes aren’t James-Bond exploits but supply-chain compromise, misconfigured cloud storage, look-alike phishing portals, and insider abuse. Despite millions invested in security infrastructure, it remains easier to hack a human or exploit human configuration errors than to break properly implemented encryption. History demonstrates this repeatedly.

Recent proof points:

The TEA App Disaster: TEA, a women’s-only safety app, suffered a major breach in July 2025 that exposed 72,000 images including 13,000 government-ID images and verification selfies, data that was supposedly deleted post-verification.

Sources: https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/social-media/tea-app-hacked-13000-photos-leaked-4chan-call-action-rcna221139 and https://techcrunch.com/2025/07/26/dating-safety-app-tea-breached-exposing-72000-user-images/

How bad was the security? The breach occurred because the database required “no authentication, no nothing” and was stored as “a public bucket” on Google’s Firebase platform. Anyone could access it.

Source: https://www.404media.co/women-dating-safety-app-tea-breached-users-ids-posted-to-4chan/

Other industry failures: AU10TIX, a leading ID-verification vendor used by major platforms, left admin credentials exposed for over a year. Identity vendors and their customers face constant phishing campaigns disguised as “KYC” (Know Your Customer) checks.

The inevitability principle. It’s not a question of if there will be breaches, it’s when. Every system will eventually fail, every human will eventually make a mistake, and every “deleted after verification” promise will eventually be tested by reality.

Think of it this way: storing your passport photo with dozens of private companies is like leaving copies of your house keys in unlocked mailboxes all over town. Eventually, someone with bad intentions will find them.

Age-assurance centralises high-value identity artefacts with a handful of processors, creating concentrated “honeypots” that become irresistible targets when controls slip.

Compliance & Data Safety Reality Check

Minimise, limit, secure. UK GDPR’s basics apply: prove you need it, take the smallest slice you can, don’t keep it longer than necessary, and protect it like it will be published tomorrow.

Deletion must be real. “We delete after verification” should mean verifiable erasure across systems, logs, backups, and vendor replicas. Controllers remain accountable for their processors. If a platform outsources age-checks, it still owns the due-diligence burden.

International transfers. If identity data goes to the US or other third countries, controllers must use approved transfer tools and complete a credible transfer risk assessment.

Safer Implementation (Tokenised Proof)

The safest way to meet the Online Safety Act’s verification demands is to avoid storing raw ID images or biometric scans altogether. Instead, platforms should use a government-brokered, short-life verification code, similar to the DVLA’s share-code system.

Here’s how it could work:

- User initiates verification. The platform directs the user to a secure government portal (just like the DVLA site).

- User proves identity to government. Instead of uploading a passport scan to a private vendor, the user provides a small set of knowledge factors already known to the state. For example:

- National Insurance number (issued before age 16 in the UK)

- Driving licence number or other official reference (passport, citizen ID, etc.)

- Postcode registered to their official record

- Government confirms and issues share code. If the details match, the system returns a single-use verification token with a short expiry time (e.g., 24 hours).

- Platform validates the token. The platform checks the code’s validity against the issuing government API, without ever seeing or storing the underlying ID document.

Why this works:

- No honeypots. Raw ID never touches the platform or its private vendors.

- Safer for business. Companies avoid the liability and security costs of storing sensitive documents.

- Cheaper and scalable. No need for expensive biometric systems or vendor contracts.

- Audit-friendly. In the event of a security incident, investigators can re-check the token’s issuance in government records rather than digging through vendor databases.

- Universal coverage. Every UK resident has an NI number by 16; under-16s could be verified via a parent/guardian token or a linked educational record.

- Built-in expiry. Tokens expire quickly, meaning stolen codes are useless to attackers.

This isn’t unprecedented. The DVLA’s share-code model proves this is possible today: https://www.gov.uk/view-driving-licence

The government already had GOV.UK Verify (though flawed in implementation) which showed they understand the concept of federated identity without raw document storage.

Expanding the DVLA approach to cover NI numbers and other state-held records would let the UK meet the Act’s safety goals without creating sprawling archives of sensitive personal data in private hands.

Conclusion & Call to Action

Protecting children online is essential, but poorly designed measures can harm everyone. The Online Safety Act forces millions of UK adults to surrender their most sensitive personal data to private companies with patchy security records, creating vast honeypots of identity documents that will inevitably be breached.

We’re sleepwalking into a surveillance state disguised as child protection. Every platform you use, every game you play, every community you join will soon demand your passport photo and a selfie. This data will be scattered across dozens of vendors, processed in multiple countries, and retained far longer than promised.

What Tech-Savvy Kids Are Already Doing

The predictable workarounds are already happening. Since enforcement began, we’re seeing exactly the behaviors experts warned about: children and tech-savvy adults using VPNs to bypass checks, fake license screenshots circulating online, computer games exploiting adult facial images to fool verification systems, and countless other clever workarounds.

VPN usage has exploded. ProtonVPN reported a 1,400% increase in UK sign-ups after the Act came into force: https://www.theregister.com/2025/07/28/uk_vpn_demand_soars/

Half of the top ten free apps on Apple’s App Store are now VPNs, with downloads up 1,800% in some cases.

Now the government is considering banning VPNs entirely. Labour MP Sarah Champion has campaigned for VPN restrictions, and Technology Secretary Peter Kyle says he’s looking “very closely” at VPN usage: https://www.techradar.com/vpn/vpn-privacy-security/could-vpns-be-banned-uk-government-to-look-very-closely-into-their-usage-amid-mass-usage-since-the-age-verification-row

This would be a cybersecurity catastrophe. VPNs are essential security tools used by businesses and individuals to protect sensitive data on public WiFi networks. Banning them would force the UK to join authoritarian regimes like China, Iran, and Turkmenistan while making everyone more vulnerable to cyber attacks. Any cybersecurity professional will tell you: never connect to public WiFi without a VPN, or you’re asking for your details to be leaked.

Rather than building healthy digital habits, the Act is inadvertently teaching an entire generation to circumvent security measures and normalise deception as a digital life skill. These workarounds don’t just undermine child protection, they erode trust between children and parents who discover their teens have been using sophisticated privacy tools to access restricted content.

The government seems hell-bent on this legislation despite lacking basic digital knowledge themselves, despite the bill being discussed and revised via committee over a decade in the making.

The window for change is closing. With enforcement already underway and platforms rushing to comply, we need immediate action before this becomes irreversible.

The harsh reality of what you can do:

- Transparency demands will largely be ignored. Most people treat privacy policies like game terms and conditions… nobody reads them, they just want immediate access and will take the path of least resistance. Companies know this and will simply say “comply or you can’t access our content.” It’s a monopoly disguised as choice.

- “Choosing carefully” isn’t really a choice. Xbox will likely use one vendor for age checks. Discord will use another. Reddit another still. You can’t meaningfully choose alternatives when each platform picks its own verification partner and demands compliance for access.

- Contact your MP immediately, this is your only real leverage. The parliamentary petition to repeal the Act has over 500,000 signatures, but the government refuses to listen: https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/722903

Demand they implement a tokenised, government-brokered verification scheme like the DVLA share-code system before more private honeypots are created.

- Spread awareness before people sleepwalk into surveillance. Most people don’t realise what’s happening until they’re forced to upload their passport to play a game or join a community. Share this with friends, family, and colleagues before they discover their government ID is now scattered across multiple corporate databases.

There is hope for change. Public pressure has successfully rolled back digital surveillance measures before, from the abandonment of ID cards in 2010 to recent victories in data protection law. The 500,000+ petition signatures show the appetite for change exists.

The choice is ours: effective child protection through smart government systems, or a privacy nightmare that exposes everyone’s identity to the highest bidder while failing to actually protect children. But we must act now, while there’s still time to change course.

What’s your take? How else might we protect both privacy and children online? What changes would you want to see? Let me know in the comments below.